- ActionsDate de l'événement

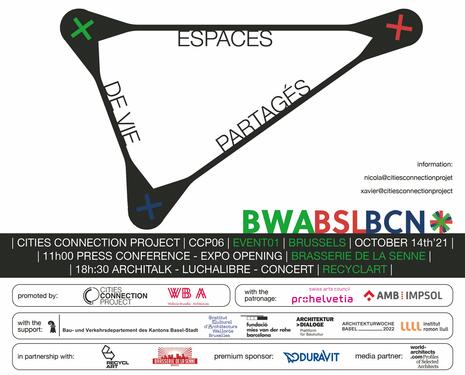

14-15/10/2021Site Internet

Published on 15/09/2021

Starting from the common place

© WBA Let's begin from a common place. The period during which the selection of these twenty projects took place. That moment when "The expression 'living in a globalized world’ suddenly got old," as Bruno Latour(1) observes. As we sheltered from the Covid-19 pandemic within our four walls, we all became aware of the importance of our living environment. It became easier to grasp because, on the one hand, it was limited by the restrictions on going out and its spatiality thus became more sharply defined, and, on the other, we were forced to live that spatiality on a daily basis and share it every day with our " bubble" (term used by the Belgian government to designate the number of people we could host at home). Beyond this bubble, we became more aware of our shared living spaces insofar as they were lacking or constrained us in our behaviour. “'Territory', that administrative word, acquired for the confined an existential meaning. As if instead of being drawn from afar by others, from outside and above, we could describe it for ourselves, with our neighbours, from within and from below,” Bruno Latour(2) continues. This shift in perception undoubtedly influenced the selection of the twenty shared living space projects that came out of the Wallonia-Brussels Federation. This federated community of Belgium governs the French-speaking territory of Belgium and represents an area of approximately 17,062 km². It thus encompasses the metropolis of Brussels as well as medium-sized towns and villages, spread over landscapes of lowlands and hills.

The selection reflects the diversity of these contexts. It prioritizes architectural forms that enhance their uses, whatever the scale or programme. Thus, the neat finishes of a sports hall have a soothing effect; at the edge of a wood, the roof of a childcare centre as thin as an origami fold recalls the archetype of the shelter; elsewhere, spaces transformed into glazer classrooms or offices are like interior windows allowing the gaze to traverse and thoughts to wander. All these details anchor us to one place in order to better open up onto the otherpeople.

The common areas of the collective housing presented engender the same capacity to initiate encounters and create the common. DXA.archi, for instance, achieves a smooth, benevolent transition between the private and public areas for the disadvantaged people of the multigenerational housing of the La Perle project. The architects of LRA insert stacked staggered dwellings into an old industrial shed to form a sky-lit central interior street. The proportions and widenings of this street are reminiscent of those of medieval streets or medinas. The street thus avoids monotony, generates encounters, initiates stories.

The same efficacy is found in Ouest’s project for the Le Rideau theatre. The insertion of a patio enables the tying together of the five buildings occupied by the theatre, and, moreover, offers a visual porosity between the different spaces that compose it: from the street to the performance space. In Fosses-la-Ville, the architects of RESERVOIR A succeed in overcoming the inward-looking spatial logic of the grounds of a château by creating a diagonal axis on the plot on which the new building sits, thus opening the park to the community and joining it to the city.

A series of other projects is based on citizen participation to “form community”. This is particularly the case for several public spaces such as the "urban carpet" deployed by the studio K2A in a square in one of the nineteen Brussels municipalities. Development of the project in conjunction with the users enabled an intervention that greatly enhances the original strength of the place. Based on public consultation, the studio Suède 36 has made the centre of the small town of Saint-Hubert again a place to stop and stroll about. The Quatre Tourettes project in Liège by Du Paysage, for its part, illustrates the studio’s "firm conviction that exchange and encounter are the raisons d'être of public space"(3). A conviction shared by B612 in the development of the one-hectare Fontainas Park in the centre of Brussels. Here, the architecture of the new programmes is buried or becomes an urban marker to highlight the link between this new public space and the existing urban fabric.

This participation is also found in advance of the project, as in the commune of Berloz, where residents’ input is essential to the planning and competition for a multiservice rural house. The architectural resolution of the temporary association HE-Architectes and Georges-Eric Lantair adds, through the keenness of its reading of the place and its resolution, value to the public space, proposing a building and a square in harmony with the village’s other points of reference. An urban insertion was also sought by the studio V+, which transformed a commission for the enlargement of a museum into an activation of former industrial blocks in the town of Mouscron. To further anchor this intervention in the lives of the inhabitants, Simon Boudvin, the artist appointed to set the standards for the integration of artworks to which all Belgian public buildings must comply, "sees this facade as a sort of architectural palimpsest"(4). He and the architects recycled 30,000 bricks from eight demolition sites in the area to form the building’s envelope.

These twenty shared living spaces are not limited to common places. They invite us – through the relevance of their approaches and the architectural attributes put in place – to pause, to exchange, to create something in common and, for some, to form a community. Since they are conceived of and designed "from within and from below", they represent so many ways to achieve a densification of our built territories on a human scale.

By Audrey Contesse, Director of the Institut culturel d’architecture Wallonie-Bruxelles (ICA).

(1) Bruno Latour, Où suis-je? Leçons du confinement à l’usage des terrestres, ed. La Découverte, 2021, p. 92.

(2) Ibid, p. 93.

(3) Sophie Dawance, Reformuler la question, in Architectures Wallonie-Bruxelles, Inventaires #2 2013-2016, edited by A-S. Nottebaert and X. Lelion, 2016, pp.106-112.

(4) Pierre Chabard, Instance d’un trajet d’architecture, in V+ architecture. Documents on five projects, 2015, p. 138

- ActionsDate de l'événement

09 & 10/05/2025Published on 07/04/2025

-

Rotor et A+ Architecture in Belgium à Venise

Nous vous invitons à découvrir la programmation développée par A+ Architecture in Belgium à l'occasion de la présentation de l'itinérance de l [...]

- ActionsDate de l'événement

03/04/25 - 15/06/25Published on 20/03/2025

-

Ce que habiter veut dire à Nantes

D’avril à juin 2025, l’Institut Culturel d’Architecture Wallonie-Bruxelles (ICA) vient à la rencontre des Pays de la Loire. L’exposition Ce qu’habiter [...]Exposition

- Actions

Published on 19/02/2025

-

Conférence d'Epoc à Tarragone

La présentation de l'exposition Cities Connection Project#7 au COAC de Tarragone qui se déroulera du 20 février au 3 avril 2025 est l'occasion d [...]Cities Connection Project