- PostsSite Internet

Published on 01/04/2014

Sustainability through Rotor's eyes

© Istvan Virag Behind the Green Door started out as a research and exhibition project. The publication of the book, as a kind of commemorative catalogue, marks a high point in this process, and not necessarily its end. The exhibition conceived for the Norwegian Centre for Design and Architecture as part of the Oslo Architecture Triennial, is currently on display at the Danish Architecture Centre (DAC) in Copenhagen, before possibly continuing its travels.-----It is hard to say how future generations will judge our era, but there is a good chance that our quest for sustainability will be on their list of key features. Seen on a broader timeframe, the trend is still in its infancy: only a few decades ago, the notion of sustainability was simply non-existent. For tomorrow's historian, the architecture of our age will offer a fertile field of study. Building remains and archive materials will show how our civilisation did its best to put its quest for sustainable development into practice in the physical world. Behind the Green Door adopts a similar perspective to explore how we design and redesign our buildings and cities to reflect our yearning for a sustainable world. The book aims for a certain detachment towards the subject - that of an archaeologist or anthropologist from another realm – thus offering a fresh take on an issue to which we are all too familiar with. We look at fragments of the present as if we had just unearthed them in an attempt to preserve our sense of awe and wonder.

At the root of this research project lies a question that we have been asking for some time. The quest for sustainability has become an incredibly strong force in today's societies. It shapes policymaking, the economy, our daily lives. So what can explain the “sustainability fatigue” that has surfaced in the world of design, and of architecture in general? Why this sense of unease or irritation? And once pinpointed, what is the best way of addressing the issue and getting it back on track? This book sets out to come up with some possible answers. The reader will find 600 items that serve as a body of evidence. They take the form of physical objects (models, samples, original sketches, etc.) and digital objects (photographs, films, virtual images, etc.). None of the artefacts have been custom-made for the exhibition; these are documents that were created for reasons other than to serve our narrative.

To put together our collection, we first looked at a broad variety of projects that claimed, in some way or another, to be sustainable. Rather than start from our own assumptions as to what constitutes sustainability and then looking for good examples to illustrate our point, we chose to set off on a quest for projects already labelled as such. We covered a vast territory, as the projects under consideration were not necessarily all architectural. They included campaigns by groups of activists, products from the construction industry, software geared towards designing green architecture projects, initiatives by local authorities, citizen movements, etc. We limited our search to the last five decades that have spawned solutions to “save the planet”. It is only logical that these only appeared with the dawn of a more widespread recognition of the environmental issue, namely towards the end of the 1960s, according to the historians of the ecological movement. For every project we chose – and this was always an intuitive, but collectively endorsed decision – we contacted its authors (architects, engineers, industrial groups, etc.) and asked for a list of original documents illustrating the project. We shortlisted these, selecting objects that best convey both the project's ambitions and the challenges to those ambitions. This arduous task resulted in a broad collection that we slimmed down to an even 600 items, a randomly fixed number that nevertheless intuitively felt optimal. We needed sufficient samples to give a true and fair view of the broad spectrum of approaches to the topic. At the same time we had to make sure that the visitor/reader did not get lost in a maze of different narratives.

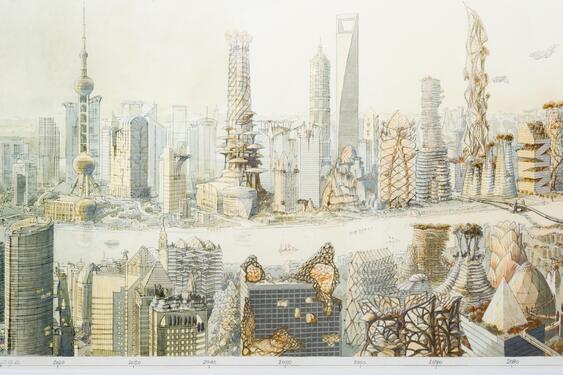

In the book, as is the case for the exhibition, the 600 items are split into two sections. In the first section, the Tables, exhibits are shown in clusters of 10 to 20 items. These objects reinforce each other; they speak jointly on common subjects, often from very different perspectives. In the second section, Collection, the objects are laid out in a long, uninterrupted sequence, progressing chronologically from 1968 to 2055. Like a museum store put on display this section reflects the randomness of the original database. We tried to accompany each object with enough information for the reader to quickly grasp its relevance. At the same time, we wanted to avoid a one-dimensional reading. Each item displayed has its positive side and its down side, and both remain apparent. It is up to readers to reach their own conclusion. Rotor sows its own thoughts in the course of the book, in particular in the Tables section, but without claiming a monopoly. More than a hundred international experts were invited to share their view on the items. A few weeks before the final edit, we sent them a draft manuscript, asking them to provide us with brief comments at precise points. Most of these comments have been integrated into the final version of the book, in the places pinpointed by their authors. The reader will therefore find a presentation with multiple voices that do not necessarily sing in harmony, far from it. And that's the whole point of the exercise.

Labelling a project or product as “sustainable” is only possible if we carefully define the framework within which this assessment is made. Each of these frameworks implies a bias in relation to what we understand as essential needs, before being able to define how to come up with a “sustainable” answer. The competition between these frameworks is a fundamentally political debate: it raises the question of how each defines an ideal world. In practice, this debate is rarely heard: we prefer not to show dissensions within the same team (“all in favour of a sustainable world”). Consequently the half-hearted consensual frameworks are those that win through. The race for energy efficiency, for example, is popular for the simple reason that it is apolitical: it makes it possible to sidestep the question of the legitimacy of needs. It simply calls on everyone to carry on the same, with less energy.

By comparing different points of view, sometimes opposed, put forward by players who have all nevertheless signed up to sustainability, Behind the Green Door tries to restage conflicting ideas, to breathe new life into a debate that had become anaemic. Many players try to convince you of the contrary but nothing is self-evident in the quest for sustainability. However, in no way does it mean that the quest is in vain.Lionel Devlieger - Rotor

- BilletsAuteur

Audrey ContessePublished on 09/10/2018

-

Allier procédure et processus

"La scène belge est gage de qualité, d’humanisme et de poésie" peut-on lire dans le numéro 425 de l’Architecture d’Aujourd’ hui, dévolu à l [...]

- BilletsAuteur

Emmanuelle BornePublished on 06/07/2018

-

Belgitopie

Faut-il se fier aux expositions internationales, a fortiori à la Biennale d’architecture de Venise, pour appréhender les mouvements de fond et enjeux [...]